Does anyone ever feel comfortable talking about sex? We are so afraid to talk about it openly that we always distance ourselves from the subject. Only behind closed doors and underneath bedsheets does sex ever come closest to its intended purpose. A naked truth left for naked bodies. A truth as pure as a trickle of saliva. But we all know that this truth is not so pure, or at least all these other overwhelming narratives confirm the worst of sex. I do not need to go into detail about them. You know them. Predators take advantage and victims are blamed. These narratives are so exhausting that fiction deserves new imaginative forms for new realities. And Valerie and Her Week of Wonders is that new reality I so long for.

Before I begin my review, I have to acknowledge the historical backdrop of Czechoslovakia in the 1970s under Soviet rule. If not for the Prague Spring – a period of political liberalization in the late 1960s – then we would not have had such a creative flourish of new films. All of which makes the French New Wave look dreadfully dull in comparison. These filmmakers fought for more than just film techniques. They fought for an artistic expression that could not be realized with socialist realism, a form of art that may just as well be called propaganda, and the only form that the Soviet Union approved of at the time. Instead of idealism, we see fatalism. Instead of realism, we see surrealism. And Valerie defies categorization of even the most obscure of isms.

To censors of the Communist Party, this film actually received a pass for being “just a love letter to European folklore”. But if we were to take a looking glass for closer observation, we would find something as radical as it is transformative. I want to stress that the Soviet Union did not care for artistic integrity or creativity. In fact, Stalin described artists in pragmatic terms as “engineers of souls”. An image that calls forth the sheen of industrial machinery and little else. I cannot say for certain what a film like Valerie engineers, but I do know that it has imbued my life with magic. The sort that only children can see.

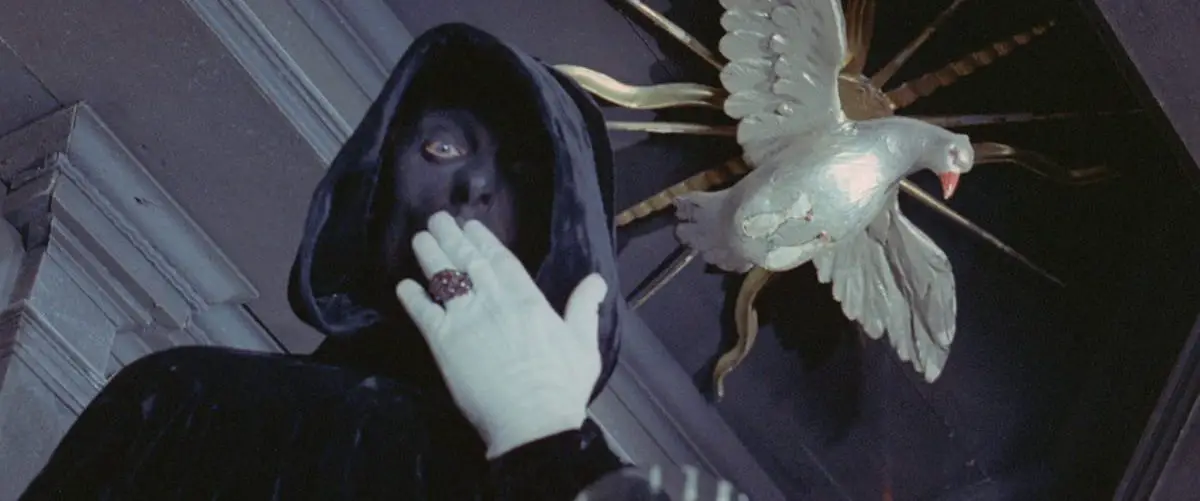

I am at a loss for how to explain this surreal film, but in its broadest sense, Valerie is a coming-of-age story. A story that just so happens to include vampires and magical earrings and a shape-shifting ferret. But before we throw ourselves down the rabbit hole, we must start from the beginning with a freshly picked daisy. Our heroine, Valerie, is blossoming into womanhood. And with womanhood comes blood on a few petals of white. However, we all know that biology cannot explain these suspect places of sex. And I would not say that Valerie merely experiences a sexual awakening. I personally do not believe that the word “awakening” does justice to sexuality when it implies a return to the world of the upright. Instead, Valerie proves that with her sexuality, she has fallen asleep into a fantastical world of all possibilities.

I do understand one common complaint about Valerie. Viewers are hesitant to give credit to a film about a young woman’s sexuality without condemning it first as exploitative. While it may be a valid concern, we cannot project 21st-century American beliefs on a Czech film from the 1970s. For one, nudity is not perceived in the same light. Eastern European cultures do not fetishize nudity. And while I do think it’s a limitation for the film to be directed by a man, I believe Valerie has one of the most honest depictions of sexuality. Co-writer and director Jaromil Jireš does not shame Valerie in any shape or form, and neither does her disorienting sexual identity stem from heteronormative undertones either. Valerie’s bisexuality is complex and has more to say in 76 minutes than most features do in hours.

READ: ‘She Dies Tomorrow’ Review: “Discomforting Yet Beautiful”

I could daydream about single stills from this film for a whole afternoon. Valerie is just that beautiful, with its soft-focus blurring of colors. At one brief moment in the film, Valerie runs through a field before a lake. I am not sure what I find so entrancing about the mist as Valerie disappears through it. It works on this mysterious subconscious level that I cannot explain. Maybe I had a dream here once. Maybe some memory of childhood has come back to me. The stroke of cold dew and grass against my legs. A sensation of the past felt in the present. I do not know. And I am okay with not knowing.

If I were to trace the plot of Valerie with a paintbrush and easel, then I imagine I would resemble a Pollock piece. Characters are always shifting identities. Boyfriends become brothers. Brothers become boyfriends. A village constable becomes a cardinal, a vampire, a father, and a ferret. Characters pass from life into death and back into life again. I am sure that somebody could psychoanalyze these relationships, but what’s the point? Again, sexuality does not belong to the rational world of the upright. Valerie experiences the world anew. Her relationships have been shaken with her newly learned sexual knowledge, plunging her once objective reality into the subjectivity of hidden desires and yearnings. Unfortunately, these fantasies can turn into nightmares too.

These nightmares manifest themselves in the repression of sexuality, and based on my definition of sex as a form of falling asleep, we see this repression actualized in waking up. Nightmares jolt us awake to our constrained reality, of the exhausting narratives of victim-blaming that I have previously discussed. And some of these narratives have some basis within the church. I should know because I have grown up as a Catholic. I am familiar with this guilt, but Valerie isn’t. She looks on at her sexuality openly, while others would much rather close their eyes in embarrassment.

Although Valerie contains a subplot based in these narratives, Jireš subverts our expectations with the inclusion of a fantastical pair of earrings. These earrings protect her with magic. Valerie cannot be harmed in the empowerment of her own fantasies, nor blamed for them in the pyre. In other words, these narratives cannot reach their “natural” conclusions because they have no basis in dreams. Only reality.

With that being said, Valerie accomplishes the noblest act of any film ever made. It asserts that our fantasies can shape our realities, that our fantasies can rewrite centuries of fiction that overwhelm our subconscious minds with stories of rape and sexual violence. Philomela does not have to lose her voice. Lucrece does not have to end her life. We can put an end to perversity and our conditioning to it. If only we could forget that our dreams do not have to finish with our eyes wide open, then we would have years of wonder ahead of us. Not days, not weeks, but years. One could only dream, right? – Daniel Hrncir

Rating: 10/10

Valerie and Her Week of Wonders is available on Digital HD and Blu-Ray.

The film stars Jaroslava Schallerová, Helena Anýzová, Petr Kopriva, and Jiří Prýmek.

Leave a Comment