The following review contains spoilers for Lars Von Trier’s Antichrist and features descriptions of graphic scenes.

Audacity: a hallmark of modern filmmaking, and a key part of its evolution. As the medium grows, being flashier and looser with the cinematic form allows us to see film in a new light. More contentious is the place of provocation in the movies. Purposely pushing an audience’s buttons to draw out a reaction is something that still leaves the world of criticism undecided. At the center of that conversation should be Antichrist.

To dive into the heart of darkness they call Antichrist, we have to look at its maker: Lars Von Trier. Many know this Danish filmmaker as a textbook provocateur, on and off set. His career consists of unsettling and violent films that have sparked heated debates between defenders and detractors. Conversely, his personal life has been riddled with controversial statements, reports of sustaining a hostile work environment, and recent accusations of sexual harassment on the set of his film Dancer in the Dark. To look into Antichrist is to look at the man behind it and how it uses provocation as a cinematic technique.

READ: Stay at Home Movies-What To Binge (April 9th)

I didn’t know what to make of Antichrist when I first watched it. However, it was clear that this was the work of a singular voice. Von Trier infuses the film’s unspeakable corners with energy on an entirely different wavelength from the pantheon of working figures. From cinematography that veers wildly from handheld filmmaking to painterly wide shots and a script that isn’t afraid to “go there”, it’s an unmistakably distinct piece. Which makes it all the more puzzling why it feels like two separate films: one bravely raw and one disgusting.

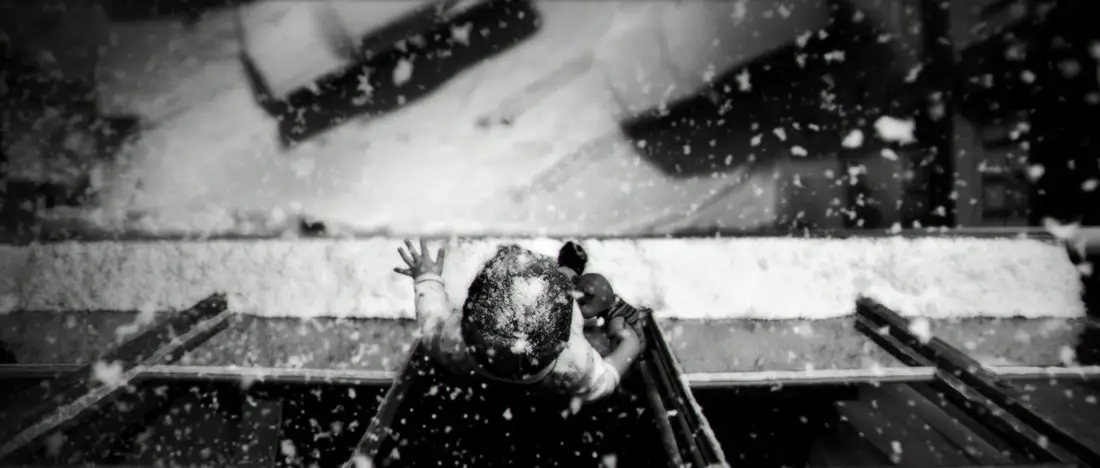

The first half of the film is one about grief, beginning with a shocking prologue. A man known simply as He (Willem Dafoe) and his wife She (Charlotte Gainsbourg) are having sex (which is actually shown on screen). Meanwhile, their child crawls out of the second-story window, plummeting to his death. In the aftermath, She finds herself unable to cope with the grief. Her unlicensed psychologist husband decides she needs exposure therapy. So the two make for a cabin in the woods of a place called Eden.

Within the confines of the woods, an intriguingly macabre scenario plays out. Though soft-spoken, Dafoe’s He comes across like a tyrant. He monitors his wife, prodding at her to try gaining insight into the mind of his “subject”. Meanwhile, She is either withdrawn, angry, or desiring of sex. The two spiral into their base desires for control and chaos, alternatively. It’s a pair of prickly performances that’s hard to shake.

The nature around them takes notice and becomes almost cruel towards them. Acorns fall loudly on their roof, a deer stumbles by He with a stillborn fawn hanging out of her, ticks cover his hands, the works. It all culminates in a scene where He finds a fox eating itself, staring at him and proclaiming “Chaos Reigns”. It’s a hard-to-shake moment indicative of the rest of the film up to this point.

Antichrist, thus far, thrives off throwing us into a building storm of grief. While shocking in moments, it never feels like it goes too far. Here’s where the second movie starts. Dafoe’s character finds the notes for the thesis he was supposedly writing. These notes include lengthy diatribes about witches and the inherent evil in women’s nature. He confronts She and after an argument, they have sex in a tree where the branches are intertwined with bodies.

This is only an omen of what’s coming. In fact, the film gets so depraved that the only way to do it justice is by describing what happens next. If you have a weak stomach, here’s where you stop reading.

Following this tree escapade, He finds out that She had purposefully deformed their child by putting his shoes on the wrong feet. She knocks him down, mutilates his genitals, and bolts him to the ground. She then mutilates her genitals, and reveals to him that she saw their child climb out the window and didn’t say anything. A hailstorm – the hallmark of witches – ravages the forest. He kills She, burns her body, and climbs out of the woods before a group of blurry-faced women confronts him. The End. Seriously.

Upon finishing the film, I felt a multitude of things. One was complete disgust. After presenting him as a callous, selfish man, Antichrist seemed to side with He as he feared for the evil woman coming after him. I wouldn’t quite call it misogynistic. Still, the sexual violence and, well, the entire character of She in the second half felt like it was coming from a hate-filled place.

It also felt like it was pushing my buttons for no good reason. Therefore, I considered it an example of empty provocation. A sour mark against Von Trier, despite my enjoyment of his recent film The House That Jack Built. I was ready to write the film and any other Von Trier film off entirely. That is, until I read more analyses of the film.

In an earlier article, I wrote about how reading analyses before rewatching a film can greatly change your perception of a film. Antichrist is a prime example of that ethos. Great pieces of writing from scholars, critics, and film enthusiasts alike have found a great deal of meaning in the film. Some interpret it as a modern retelling of humanity’s origins; by others as a look into misogyny inherent in religious texts.

Through rewatching the film, I arrived at a similar take on the film as many writers. Antichrist is a film about a misogynist, He, who finds himself reckoning with his deeply buried ideas of women coming to life in the form of She and the woods. But then, upon reading more about its maker, my interpretation of Antichrist gained new shades.

Lars Von Trier was diagnosed with a serious psychiatric disorder, being placed into a hospital in 2006 for a depressive episode where he wrote the film. Furthermore, this is the first in his so-called “Depression Trilogy”, which also includes Melancholia and Nymphomaniac. Then, there’s the very real and important issue of Von Trier’s harassment of Icelandic singer Bjork, mentioned earlier.

It’s not my place to make judgment on character. But the descriptions of how he treated Bjork on the set of Dancer in the Dark are inexcusable, and point to some serious issues Von Trier had with women. We will never know this man, but his later work sees him grappling with misogyny and writing the women in his movies as more three-dimensional.

As such, one can see Antichrist as a film made by someone coming to terms with their personal demons and taking on a variety of tough subject matter. It’s not empty provocation because it provokes us to think, rather than simply squirm in our seats.

I can’t say I enjoyed Antichrist, nor can I effusively praise its creator, or say that provocation will always serve a purpose. But Antichrist exists to spark a conversation. Love it or hate it, it’s a film that demands interpretation. – James Preston Poole

Leave a Comment