Perfect Blue is the debut of legendary director Satoshi Kon. Kon cut his teeth on several animated projects leading up to his first directorial outing, where he began developing themes that he would continue to circle back to during his tragically short career. Differing realities, alternate identities, cinema and life as reflections of each other… all of these are center stage in Perfect Blue. Kon had a gift to bring these weighty ideas to life through animation, the medium in which it is arguably easiest to create a different reality. Some techniques Kon uses are readily apparent, such as the use of match cuts, subjective perspective, and conflating what is happening in the media (in Perfect Blue’s case, the crime drama Mima is cast in) with what is happening to the characters in the film. However, his most effective techniques are also more subtle.

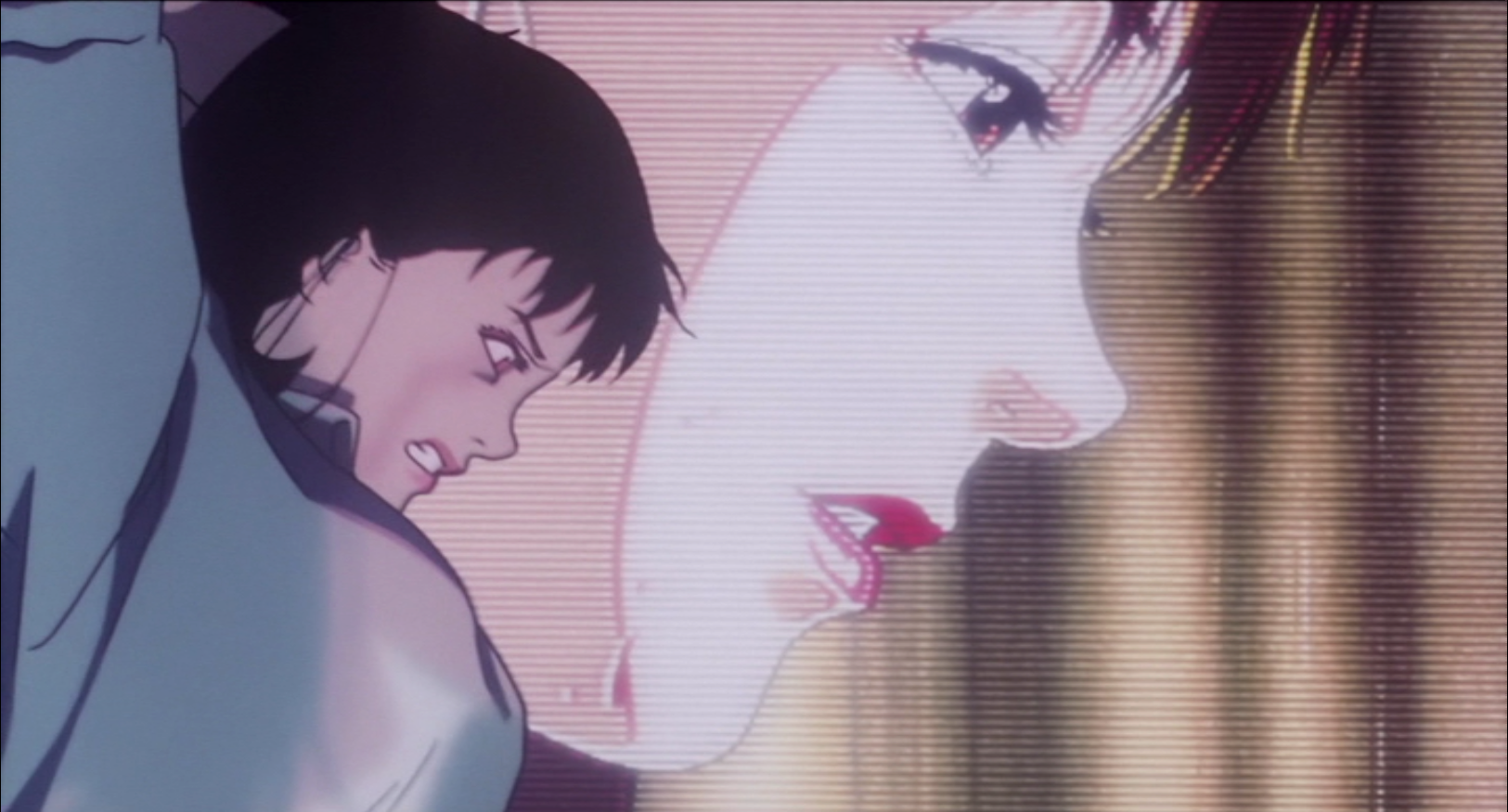

Perfect Blue is about a pop idol turned actress who has a crisis of identity when someone begins impersonating her in an online diary called Mima’s Room. This person, in addition to knowing intimate details about her life, claims to hate being an actress and wants to return to her former life as an idol. Meanwhile, Mima takes on opportunities that an idol would consider filthy: starring in a cop drama, posing nude for a magazine, and acting in a rape scene. Mima loses her grip on reality when people associated with the production of her television series get picked off by an unknown murderer. Is she Mima the actress? Mima the pop idol? Mima the murderer? These breaks with reality are primarily shown through her double, Virtual Mima: a Mima dressed in one of her old performance costumes, constantly taunting the real Mima and invading her daily life.

Freud delves into the concept of the double in his book “The Uncanny”. He describes the double as a fragment of the ego made physical, sharing “the same facial features, the same characters, the same destinies, the same misdeeds, even the same names, through successive generations”. In Perfect Blue, the ego and the double take the form of Mima Kirigoe and Virtual Mima. Indeed, Freud explains how Virtual Mima is able to know such intimate details of Mima’s life; they are born of the same ego. The double is “an object of terror” because it blends the familiar with the uncanny. This notion is demonstrated in the film through the animation techniques used to convey the two Mimas. The animation reflects reality when drawing Mima, but is stretched into the uncanny when animating Virtual Mima.

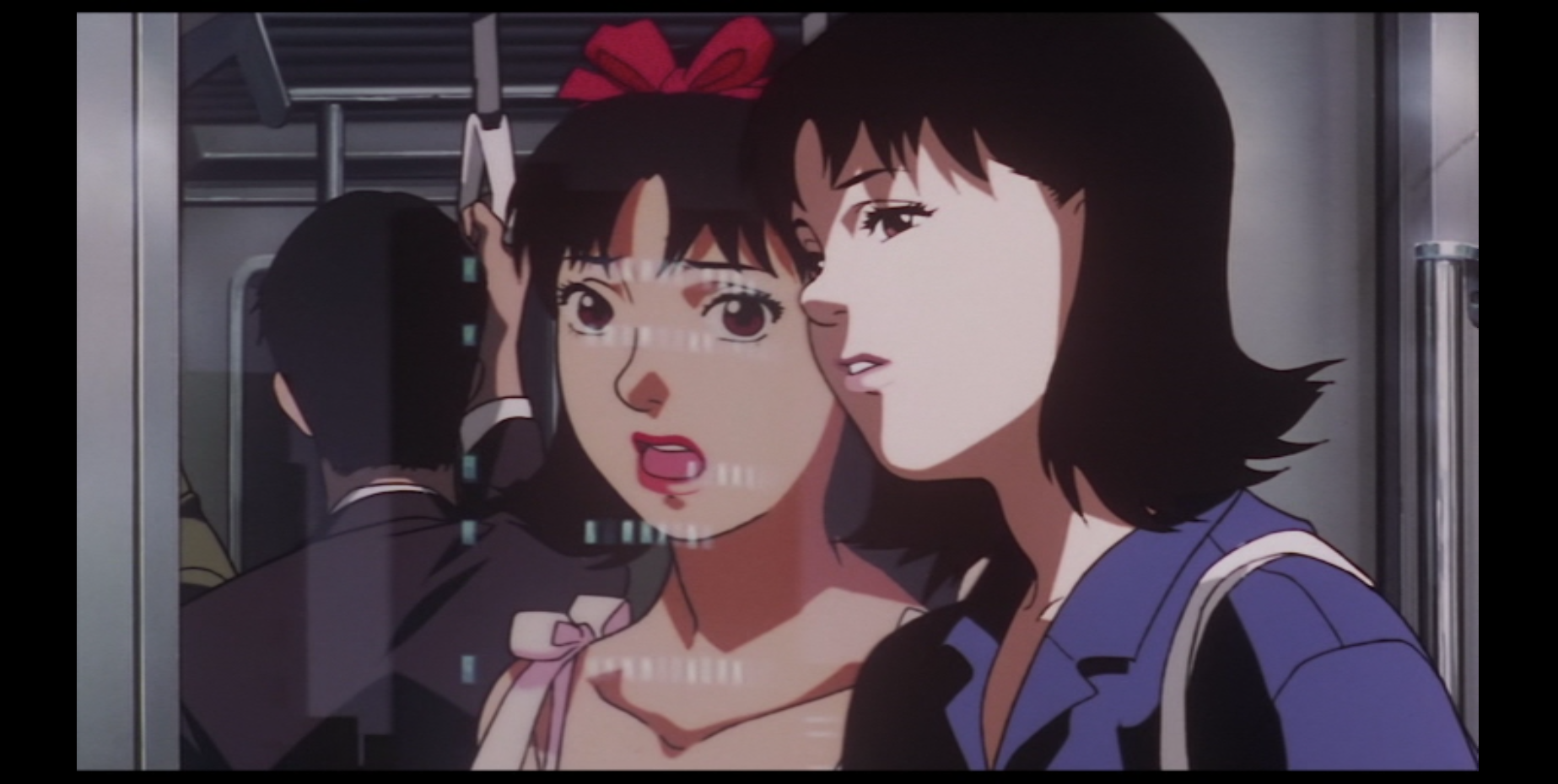

The double doesn’t manifest itself until a key point in the film. Mima has found out that her character in the drama series, who previously only had one line, was getting a bigger role. However, that role involves filming a rape scene. Mima’s manager Rumi argues with her agent Tadokoro that the role would damage Mima’s reputation, but he responds that if Mima is going to become an actor, it will involve shooting tough scenes. Mima rebuffs Rumi’s concern, saying it will be a challenge to her acting skills. However, on the train ride home, Mima’s reflection has other thoughts: her reflection turns to face her and says “No, I won’t do it!”.

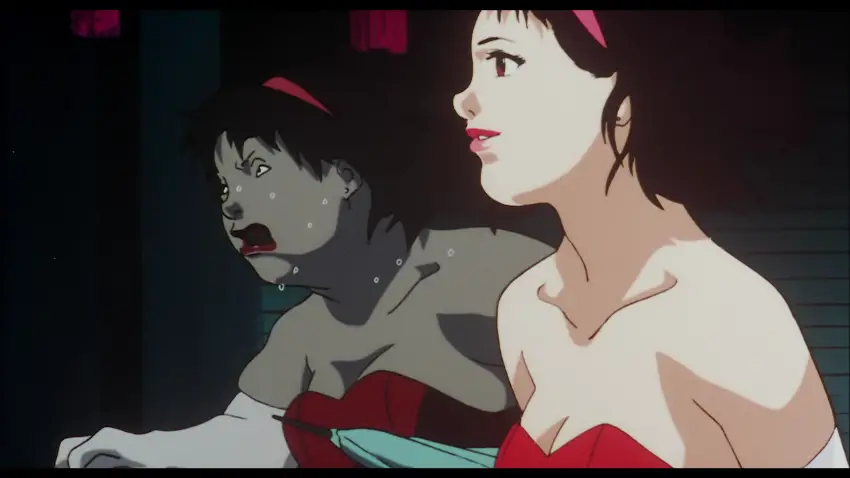

However, Mima goes through with it. Even though the scenario is fake, and Kon takes pains to remind us of this (the actor who is portraying the rapist apologizes to Mima in between shots, the director calls for the scene to reset, etc.), the emotional trauma is real to Mima. The image of her being assaulted is shown in a cluster several screens, with the entire film crew watching. Having Mima’s image tessellated over several screens demonstrates both her paranoia at being watched, but also the commodification of her new identity. This leads to Mima breaking down when she gets home. “Of course I didn’t want to do it,” she sobs into her bed. “But I couldn’t trouble the people who brought me all this way.” It is the trauma of this scene that ushers forth the physical manifestation of Mima’s madness: Virtual Mima.

Virtual Mima does not follow the same rules of reality that Mima does, and this could only be done with animation. There is an intentional difference in weight between Mima and Virtual Mima. Thomas Lamarre in “From Animation to Anime: Drawing Movements and Moving Drawings” describes weightlessness in animation as “without specific indications for direction of movement, these sketched and painted figures, in and of themselves, are oddly buoyant and light, seemingly weightless, not rooted or anchored in their environments”. Kon uses this principle to full effect when distinguishing the different laws of reality that govern Mima and her double.

Both Mimas have unique run cycles. Virtual Mima’s run cycle is her skipping with her hands clasped behind her back, so she gives the appearance of bobbing up and down as she skips forward. She flits around like a sprite, ethereal and light. On the other hand, Mima’s run cycle is frantic, her arms pumping, her hair in her face. Mima is an explosion of movement, her feet thudding against the pavement and colliding headlong into any obstacles on her path. The difference in weight between the two Mimas can be shown in the two chase segments in the film. The first segment occurs following Mima’s return to the radio station where her idol group records a radio show. She watches her old bandmates in the booth, then reels back in horror: Virtual Mima is sitting at the table with them. She drifts out of the room and Mima gives chase. In this chase segment, Virtual Mima skips over a puddle, barely causing a ripple, whereas the real Mima causes a big, clumsy splash as she runs through it. The difference in weight is meant to highlight the difference between the two Mimas: one is real and carries the weight of a real person, whereas the other is practically weightless like a hologram.

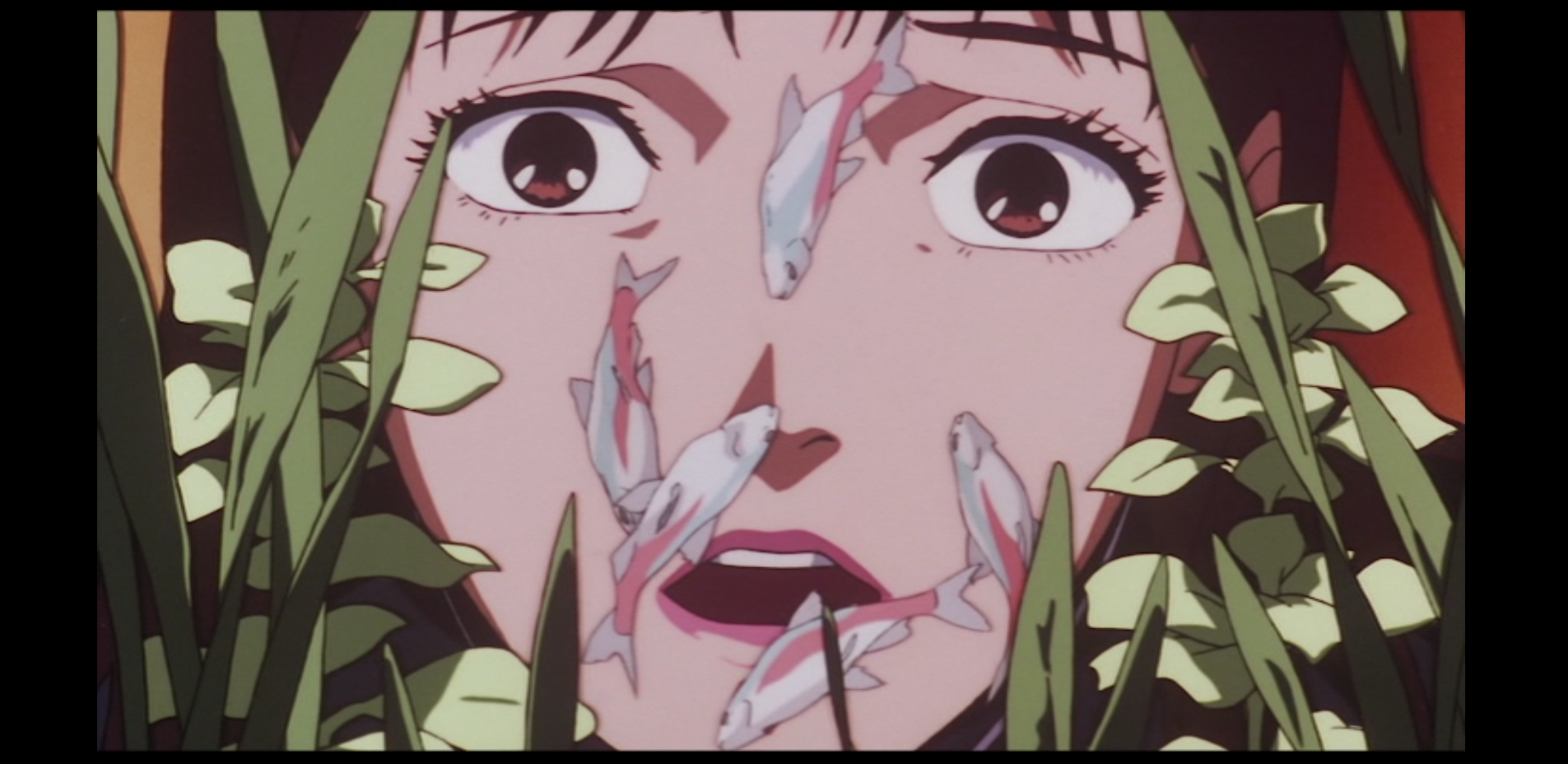

The second chase segment is the penultimate scene in the film, where it is revealed that Rumi, Mima’s agent, has been the one committing the murders and impersonating Mima. This adds another lens to the double: she is simultaneously a hologram of Mima and the physical representation of Rumi. This adds a new dimension to the weight with which Virtual Mima is animated. Virtual Mima’s weight is now conditional. Unlike the previous segment, Virtual Mima interacts directly with Mima and her environment. Virtual Mima still moves with buoyancy, but she has enough weight to shatter Mima’s fish tank with a screwdriver. Mima struggles against her, shown by her shaking arms, when Virtual Mima plunges the screwdriver through her chest. In a brilliant shot, Mima chokes out Virtual Mima, whose face morphs into Rumi’s the longer Mima grips her throat. In a later shot, Virtual Mima swings an umbrella with such force at Mima, that when the tip catches the corrugated metal wall behind her, sparks fly. Virtual Mima is no longer a hologram, hallucination, or spectre; her weight gives her a sense of reality, which means she now poses a physical threat.

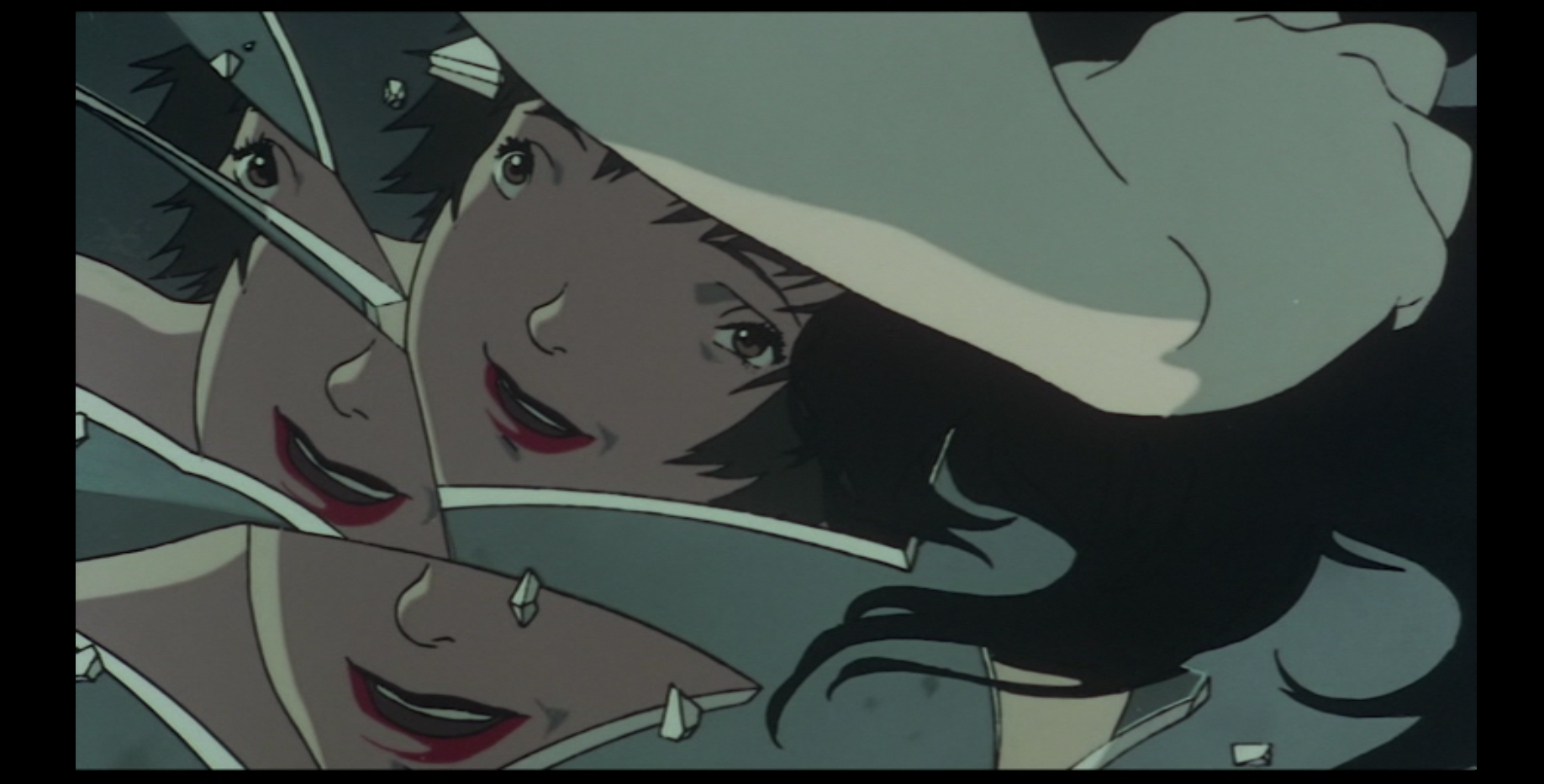

Virtual Mima’s animation in this segment switches between buoyancy and reality. This dynamic is shown in a shot of her chasing after Mima. Virtual Mima skips past a building’s reflective window in the same way she moved in the first chase segment. However, her reflection shows Rumi sweating and struggling to keep up. This shot reflects the dual realties at play in this film. Ultimately, Rumi’s weight is her undoing: while trying to retrieve her wig, she sinks her body onto a large shard of glass jutting out of a broken window. The shot holds on her face reflected in the shattered pieces, before a wave of blood washes over them.

Virtual Mima stabbing Mima with an umbrella? Real. Virtual Mima skipping over the rooftops? Fake. The double is able to touch, choke, and stab Mima, but her movements while chasing her are still languid and weightless. Her “realness” comes from the fact that the double is Rumi donning the guise of Mima’s former pop idol self. In Perfect Blue, the rules for reality are conditional, and Kon is only able to create these rules using animation. Kon’s ability to convey a subjective reality through the use of different animation techniques remains one of his strengths throughout all of his films.

Leave a Comment