I cannot bear the weight of nostalgia. Those happy remembrances, with all their reimaginings, shone more sweeter in our mind’s eye than reality itself. All the more lovelier in spite of memories only being memories. Out of grasp. Traces of light behind half-opened doors. I am not left with much of a choice on the matter, particularly when it comes to childhood. There is nothing we can do but romanticize the past on wild flowery terms. Our memory demands it, and as much as would like to think otherwise, we cannot ignore the stirrings of our hearts. We cannot think of memory as anything less than a reminder of how far we have come, of what little time we have left.

I would like to return to Australia one last time for a picnic with Nicolas Roeg’s Walkabout. It has been over two years since I last stepped foot with Miranda at Hanging Rock, and so much has changed since then, so much has been felt. Honestly, I do not have much of a record of these two years having passed, except for my few memories and reviews, the first being Picnic at Hanging Rock. In retrospect, I am so far removed from the person who once wrote that piece, with the first sentence already eluding to a long-forgotten sadness in my personal life. Although this potency may be lost to time, these memories always have a way of resurfacing from the sand like in Walkabout. A few polished bones and a schoolgirl’s pink scarf.

READ: 25 Years of ‘Space Jam’ in Four Acts

Walkabout bristles in texture right from the onset, with the sound of a didgeridoo droning its way through the city brush. As we listen to these drones, they slowly start to fall in rhythm with the accompaniment of modern life. The shuffled footsteps of commuters set the tempo. The steady march of soldiers quicken it. And a choir of schoolgirls color this sacred song with their vocal lessons, chanting the secrets of the English language with pronunciations of A. E. I. O. U. In this flurry of sounds and images, Roeg presents us with a world far stranger than the one we are accustomed to. But this is our modern world, which he has alienated from us. Our own habits may accept the supposed dignity of civilization. And yet, it seems as though our habits too form the actions of some foreign ritual devoid of spirituality. Blank as brutalist concrete.

How can I begin to describe the plot of Walkabout? Edward Bond, the screenwriter, wrote only 14 pages of script. A minimal length for a feature film, but one carefully written, with all the sparsity of symbolist poetry, though the opening minutes tell all. A geologist takes his teenage daughter (Jenny Agutter) and younger son (Lucien John) into the Australian outback for a picnic. Although this may sound idyllic, Roeg pays fine attention to all the details that can uproot the very idea. For underneath every picnic blanket there is dirt teeming with critters. Agutter squashes an ant aside with her finger. John cannot help but talk to himself, oblivious to the tension he has provoked. A plane flies overhead, a fly buzzes, a radio crackles rock into the stillness. And then their father draws a gun on his children, before killing himself.

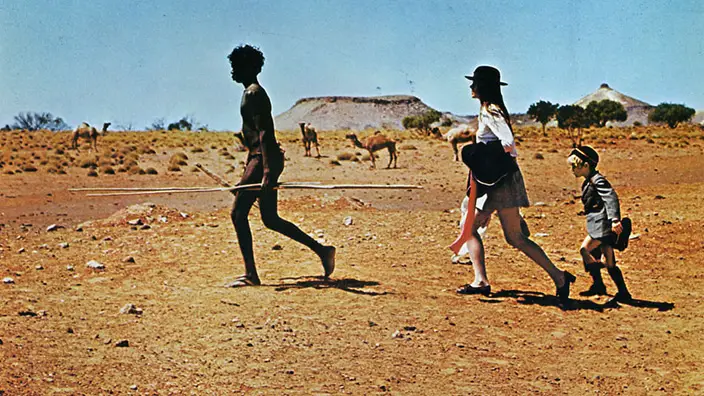

Without any moment to comprehend the incomprehensible, Agutter and John set out into the wilderness in desperation. There, they are saved by an Aborigine boy (David Gulpili), who teaches them how to survive in the harshest natural conditions of our planet. I do not have any other plot details to share with you. Walkabout can best be described as a lived memory of match cuts. Fragmented and strewn across the sand. It does not need anything other than the texture of its images to create this sensation of associative memory, of personal transformation in our characters. For Agutter, little blades of grass become trees next to toy cars. The sun puffs up into a red balloon. Even on the cusp of her womanhood, the white bark of a tree branch softens into the supple bend of her leg.

This nascent sexuality continues forward in Walkabout’s most evocative sequence, where Agutter removes all of her inhibitions for the first time, swimming in the nude of a rock pool. Her body, caught in the ripple between the surface of water and sunlight, seems so formless, so delicate among the leaves. I now understand what Impressionism meant for painters like Sir Sidney Nolan. You can see it all for yourself in Agutter’s graceful twirl of motion, where the painter’s impression of reality becomes reality itself. Accompanied by John Barry’s aching score, we then feel this strange sadness for her. We pine for our innocence, and secretly mourn the inevitable loss of Agutter’s. For we know now what we did not know then, what we cannot ever return to. The brilliance of motion and the infinite, unpredictable possibility of a brushstroke before the paint hardens and cracks.

Despite this seemingly Edenic beauty, Walkabout does not fetichize nature and childhood. Roeg does not exploit Agutter’s vulnerability for mere titillation, but he accentuates it for another effect entirely, interlacing moments of startling violence within this idyllic sequence. While Agutter swims, Gulpili hunts. Although these moments last only a few seconds each, they land as hard as the bluntness from a club swing. Nothing can prepare us for the whoosh of a spear cutting through the air and into a lizard. Flesh burnt pink. The physicality offends our senses. But who are we to judge the Aborigine people? We hunt too, with the polite, impersonal gesture of gun rounds. And as we contemplate our own perception of otherness, Agutter calls us back into the waters with our own discomfort of nakedness.

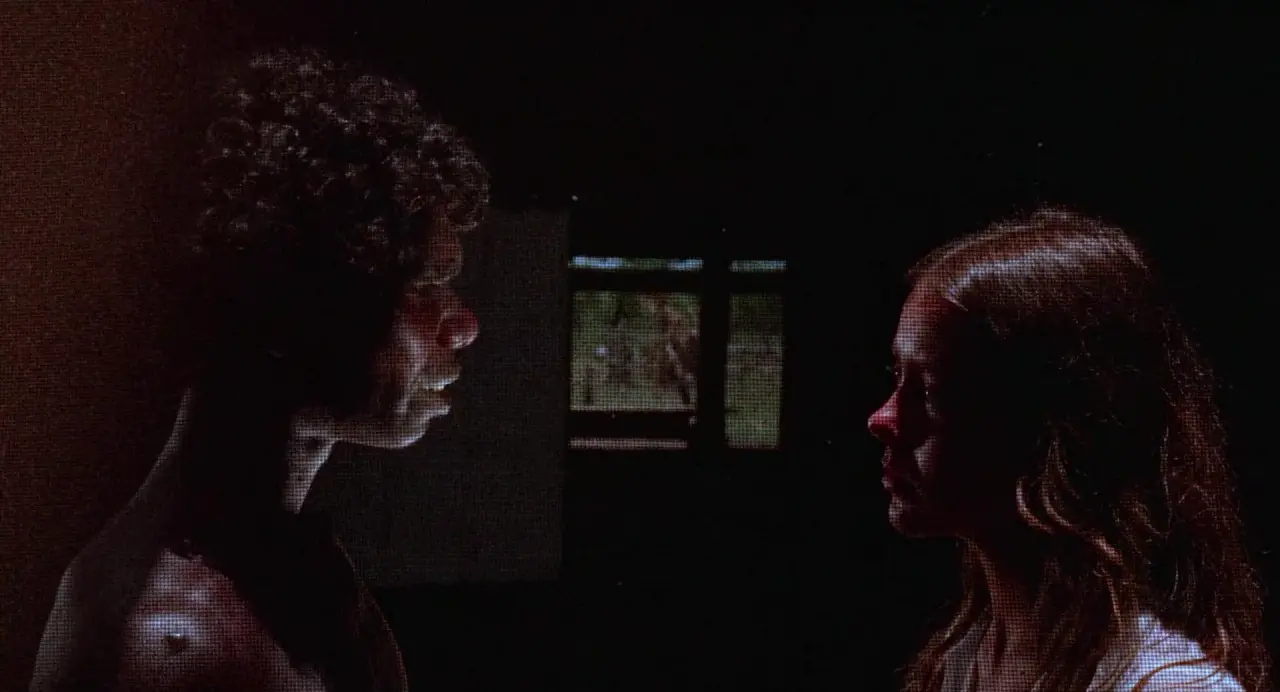

And with that, the discomfort of adolescence. The loneliness of our desires. Once dormant, now sprouting from out the earth in ecstasy like all the critters in Walkabout. Not once is this desire ever articulated, though it would hardly make much of a difference due to the language barrier. But we feel it in Agutter’s wandering eye down Gulpili’s navel. In another of my favorite sequences, they share a moment of true connection among the shards of a broken mirror. See how one trace of light hits the fragments, bursting into rainbow across Gulpili’s eyes. For a brief second, the scattered pieces illuminate a space where language breaks down, where feelings take precedence in our humanity before all else. It all makes bewildering sense, somehow. Enough to split you right open. However, very few understandings last.

Always this pang of otherness within ourselves, where no part of our identity can take root in the precarity of the future, or our already ever-changing memory. It makes sense for this pain to settle in the red sand. After all, the coming-of-age narrative finds its embodiment in the Australian landscape, with all of its dunes, drifting to the caprice of the wind. Nothing lasts for long here. A memory dusted clean of itself with swept away footprints. So when Agutter and John finally do step foot onto a real road, it feels as definite as adulthood.

I will be making that step in a few weeks to attend my dream medical school. But I don’t feel the way I am supposed to. It is not that I feel ungrateful. I just have a hard time knowing that things end sometimes. These past two years have been some of the most difficult moments of my life. And yet, even nostalgia glosses these moments clean. In fact, it is the closest our fantasies will ever get to becoming reality. Because we trick ourselves into believing them to have happened. I almost want that fantasy to continue. But it continues through what I have written and in the final scene of Walkabout.

Flash-forward some time later. In this final sequence, I see so much of myself in Agutter. She now lives back in Sydney. For her, all matters of life have been settled in the concrete of a condominium. However, it does not take anything less than the single stroke of a knife in her preparation of dinner to call her back to a time and place, where life cannot impart its stricture of a 9 to 5. The Australian outback. Associative memory, so potent in its ability to cast aside every responsibility to our present, that it crumbles everything all out of view in favor of the true intimacy of our inner world, of those precious moments of childhood before the sand became the graveled certainty of a road leading somewhere.

In her reminiscence, it seems clear to me that she may have found the road, though she is not any less lost. Not lost to the wilderness, but to time. If one single stroke of a knife can make you dumb to memory, then how can we ignore the stirrings of our hearts when we hear “the sound of a familiar laugh, the glint of eyes in sunlight, the indelible touch of a hand” from long ago? I once wrote those words in my Picnic at Hanging Rock piece, and they continue to mean something to me after all this time. Traces of who I was, of who I am now and will forever be. – Daniel Hrncir

Rating: 10/10

Walkabout is available on Digital HD and Blu-ray.

The film stars Jenny Agutter, Lucien John, and David Gulpili.

Leave a Comment